Banks play ‘mind games’ to woo customers. Big data and ‘games’ are now the tools of the trade.

Illustration: Dominic Xavier.

Pradipta Sarkar, 37, is saving Rs 10,000 every month, one-fifth of his take-home salary, in a fixed income-linked systematic investment fund to build his retirement corpus.

But being a soccer fan, his dream is to cheer for his favourite team, Germany, from stadia in the World Cup matches some day.

Would Sarkar, an information technology sector employee, set aside Rs 3,000 in high-return investment schemes, and reduce his monthly retirement savings to Rs 7,000, to materialise his soccer dream?

Banks now have a powerful tool -- behavioural science -- to figure that out. Lenders are of the opinion that by knowing short-term private dreams of their customers and giving personalised attention to achieve them, the stickiness of customers will improve.

Psychologists say there is a science behind it. “Most people tend to choose short-term goals over long-term objectives, and the propensity for immediate gratification is very powerful in human psyche,” said Dr Jawaharlal Mehta, a Mumbai-based psychiatrist.

“The downside is, when you reach the stage where long-term converges with the present, and if you have not prepared enough, you will find yourself nowhere,” Dr Mehta added.

Behavioural science is already being used for selling a variety of products, but using it for financial products is an extension of a wealth-management practice, where managers define ‘goals’ for the customer rather than returns, said a senior executive of a large private bank.

Banks in India have been using goal-oriented products for two to three years now. Some foreign banks as well as a few private banks in India could be working on knowing their customers up close and personal to boost their business. Big data and ‘games’ are the tools of the trade.

Using behavioural science as a finance tool was introduced by a Mumbai-based Indian firm, Final Mile Consulting, which claims to be pioneering the practice of behaviour architecture, applying learning from “cognitive neuroscience, behavioural economics and design”. The company now also has offices in the US, and is in high demand among top banks for their ‘games’.

“If I say you need to save Rs 8 crores for your retirement, you will give up immediately. But if I can show you through a game that you have enough resources right now to ensure that amount is accumulated at retirement, your expenditure and saving pattern will change,” said Anurag Vaish, co-founder of Final Mile.

Interestingly though, by simulating the sacrifices to be made to reach one particular objective and offering other interesting side objectives, the ‘games’ tend to bring out the hidden desire of a person.

“These are typically 20-30 minute games, but every time, the gamer tends to come up with a different conclusion about her life than what was there in her mind always. It is the right thing to say you are saving for your daughter’s education, but it turns out you really want that Ferrari,” Vaish said.

In developed markets, banks take these games and offer them to their customers through their own application. When the customers play the game and agree to share their data with the bank, the wealth manager steps in.

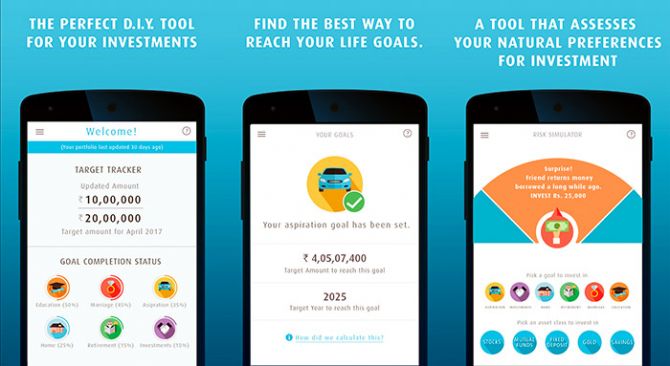

Final Mile has now partnered Transunion Software Services to develop a similar application for the local market. Called WealthMapp, the application can be downloaded from the Google Play Store for free.

The application is not linked to any bank, and it doesn’t share the data with any bank. It offers a dashboard where a customer can plan her goals and know the approximate monthly savings needed to achieve that. In the back-end, the application is connected with a whole host of global economic databases, so that it can work out an approximation of the present cash flow needed to achieve something after a set period. The application does not dig for customer’s personal data, but works on the figures put in the app.

It is essentially a version of a ‘game’ and this can reveal much to the customer as well as to data aggregators, in this case TransUnion. For example, TransUnion can gauge the saving pattern of a set of customers from a particular socioeconomic background and location, and age group.

Shaleen Srivastava, head of solutions and alternate data at TransUnion, said the data would be used for creating different models, but unless the customer directly wanted, the data would never be shared with any bank.

So, if somebody wants to save enough to send her daughter to a college in the US, the app will extract education inflation and other costs, and present an approximate amount to be saved every month. The app itself would sit unobtrusively in the mobile phone, alerting the customers if some lead economic indicators change.

“But it won’t be much. You don’t expect the US education inflation to suddenly shoot up to 10 per cent from, say, 2 per cent now. Maybe it would be 2.1 per cent, in that case the app will tell you that you would need to save Rs 100 more this month,” said Vaish.

It is quite likely that the next set of product planning offering by banks would be on the lines of the WealthMapp application.

© 2025

© 2025