| « Back to article | Print this article |

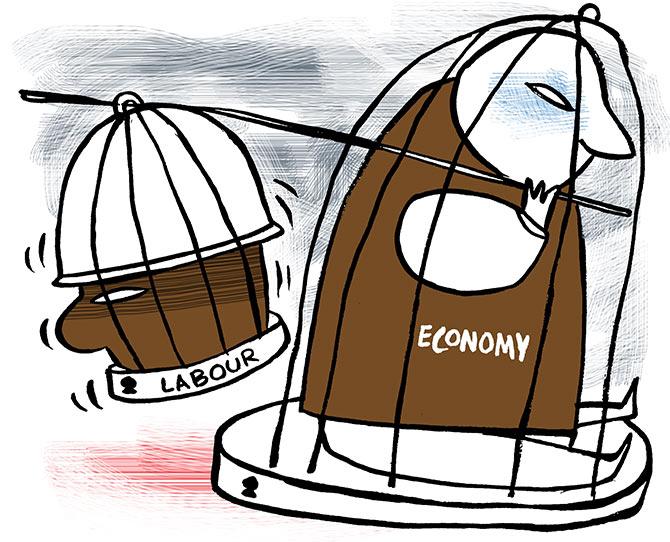

Labour law changes for three years may not be enough as it takes a couple of years for factories to build and operations at a proper scale start only in the third or fourth year.

When Madhya Pradesh Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chouhan went to town about a sea of labour law changes he has to offer to new businesses, he wasn’t probably aware that a tsunami was coming his way.

Labour law reforms, a forever demand of the industry, has always been a sensitive issue in India and for a chief minister to announce major pro-business changes to the labour laws through a press conference on May 7 was a rare sight in India’s recent political history.

Later that evening, the Uttar Pradesh government issued a press statement about a flurry of decisions taken by the Yogi Adityanath-led Cabinet.

It was a 13-page press release related to 10 announcements.

Though the decision to abolish almost all labour laws in the state for three years was the most significant, it found place in the press release on page number 11.

The state government has justified the need for such a radical move to providing jobs to a large influx of migrant workers, who have returned home and would be left jobless due to the ongoing pandemic.

While the MP government has already brought about some changes through an executive order, the UP government chose to go for an Ordinance, which is now pending with President Ram Nath Kovind for approval as it requires tweaking of central laws applicable there.

Forget policy observers, it took even some of the industrialists by surprise, especially since it came from a non-industrial state, which essentially supplies labourers to industrialised states in large numbers.

The announcement caused a chain reaction, with Gujarat CM Vijay Rupani announcing the next day that the state will exempt new companies setting units in one year from almost all labour laws for 1,200 days.

It moved quickly and the Ordinance is pending the President’s approval.

Even the Congress-ruled state governments, such as Rajasthan and Punjab, have gone into a huddle to consider some of the changes being made by their BJP-led counterparts.

But it is unlikely that these states are going to follow the UP model, that the state's labour department officials termed as “drastic".

At least officials of the Karnataka government have made public statements, saying labour laws won't be abolished in the state, though some changes are planned.

The central government wasn’t caught unawares.

The Union Labour and Employment secretary Heera Lal Samariya told industry chambers at a meeting on May 8 that the government is working closely with states on labour law changes, referring to the announcements made by UP and MP.

In fact, it was none other than Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who gave a pat on the back of Rajasthan CM Ashok Gehlot during a meeting of chief ministers on April 27 as he hailed the state government’s move to increase the daily working hour cap from 8 to 12 hours to compensate for the loss of production.

At present, 10 states in India have taken a similar step (unlike Rajasthan and Punjab, not all states are offering overtime wages).

US-India Strategic and Partnership Forum (UISPF) president and CEO Mukesh Aghi welcomed the initiatives taken by the state governments and stated India needs to move away from “the 18th-century guidelines".

Giving flexibility to companies to downsize staff during times of stress is on the top of his checklist for labour law reforms as he mentioned that UISPF was in touch with many state governments in India to look at investment avenues, he said in an interview.

According to the Industrial Disputes Act of 1947, all companies hiring at least 100 workers need official approval for retrenching workers (though as many as eight states in India have a relaxed regime, compared to the central law with a threshold of 300 workers now).

Aghi also demanded the “inspection raj” be abolished and emphasised governments need to act quickly as investors are moving to countries like Vietnam and Cambodia.

He, however, said that businesses would look for a stable policy environment more than anything else.

“We need a predictable and transparent policy environment based on consultations.

"The biggest challenge would be to get a sense of transparency and the government needs to send a strong message in that direction,” Aghi said.

Even he admitted labour law changes for three years may not be enough as it takes a couple of years for factories to build and operations at a proper scale start only in the “third or fourth year.”

“This is an issue of policy predictability. We need permanent changes, which should be conveyed to potential investors to build confidence,” he added.

“Obviously, we need labour market reform,” said Bibek Debroy, chairman of Economic Advisory Council.

“We need to make organised labour market less rigid and extend protection to the unorganised labour market. But we need to start from the first principles.”

He agreed that the abolition of labour laws for a period of three years would be of little help and will set a time frame for state governments to re-look at the labour laws holistically.

Radhicka Kapoor, senior fellow at Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations, said the government has to create policies for boosting demand and one of the ways was to give higher wages in the hands of the working class, which has been left vulnerable due to the pandemic.

“We seem to think that labour regulations are the only binding factor in India for investments but that’s not correct.

"There are too many bottlenecks. The quality of infrastructure on offer is an important element to attract investors - we have expensive power supply and poor road logistics,” she said.

Debroy gave the example of Bangladesh, which did a holistic restructuring of its labour laws and came up with a single code in 2006.

He said India can begin by looking at the model proposed by the Jammu and Kashmir government in 2018 (before it was dissolved).

It had announced a uniform Employment Code encompassing all the labour laws in the erstwhile state.

After coming to power in 2014, the NDA government at the Centre had proposed to convert 35-odd labour laws into four codes, one each on: Social security, industrial relations, wages and occupational safety, and health.

While one has become a law, the other three have been introduced in the Parliament.

But for now, it seems the Centre is not willing to bite the bullet.