What India should not do is take the path China took at one stage to become the world's foremost cheap factory, says Subir Roy.

What former President A P J Abdul Kalam, a prolific writer, had to say on choosing the right path for India's development has turned more relevant with glimpses into the contents of his last book Advantage India being published posthumously.

Most relevant are his views on how the signature policy initiative of the Narendra Modi-led government, "Make in India", should be pursued.

While seeking to turn India into a global manufacturing base is quite "ambitious" and there is need for "high aspirations", one pitfall in particular has to be avoided, says Kalam.

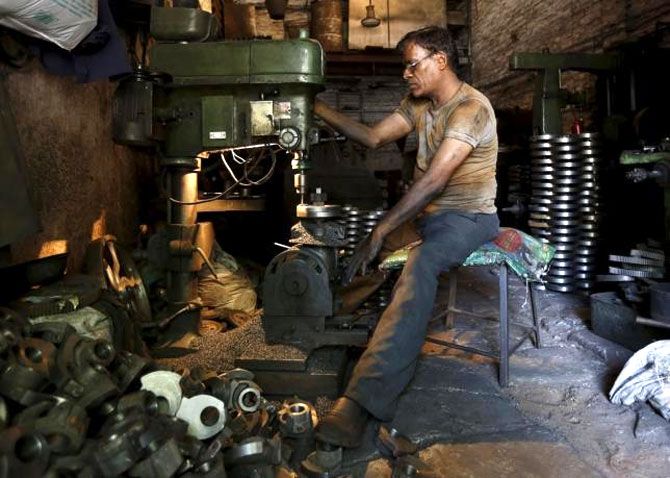

India must not become a "low-cost low-value assembly line" for the world as that would impose "a great price and pain to the people".

The correct path, according to him, lies in going for original research to design, develop and manufacture in India by using its energy (youth), unique store of knowledge (wisdom of the ages) and institutional strength (democracy).

What follows from this is that India should celebrate its start-up momentum and build on the information technology services capabilities that preceded it.

What India should not do is take the path China took at one stage to become the world's foremost cheap factory.

Now that China is seeking to vacate that space as its labour costs are rising, it would be shortsighted for India to try to simply step in.

To illustrate this, look at garment exports. India has been a laggard in it and China, till now a front-runner, is shedding some of its low-value capacity. This space is increasingly being taken up by countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam. Should India try to compete for this former Chinese business?

No. For one thing, wages in Bangladesh are lower than in India. What India must strive for is higher value addition, productivity and price realisation to pay for its higher wages.

To achieve this, India needs to urgently upgrade the skills level of its manufacturing workers across the board. In fact, this needs to be given perhaps the highest priority. Without workers with the right skill and discipline, India cannot aspire to any kind of a status as a preferred manufacturing destination.

This is well known but needs reiterating as at times it seems "Make in India" is being sought to be achieved as a one-step exercise. Get foreign direct investment which will result in setting up of factories and bingo you have "Make in India".

Top executives of the National Skill Development Corporation have just resigned. Unattributed news reports indicate that the new minister is unhappy with the pace of progress achieved.

He is entitled to put his own men in his domain (that is one of the goodies that come with becoming a minister), but his track record does not indicate he has any special skills needed to energise and expand such a huge operation.

Perhaps the most important point that Kalam has made is the need to mobilise Indian research skills to come up with components of the long supply chain for manufacturing as also final products.

This places a tremendous premium on designing to innovate products as also to develop processes. For this you need higher education and applied research capabilities which China developed in plenty and India critically lags.

Indian entrepreneurs have to take the lead in this while getting research institutions involved. Indian skills in information technology and engineering design will also have to be brought in. The overall point is that for manufacturing to take root in India the Indian entrepreneur has to buy into the idea.

When Kalam warned that embracing low-value low-cost manufacturing would be at great cost and pain to the people of India, many costs can be visualised.

The most obvious is the cost to the environment, climate and public health. If a lot of the world's polluting and resource-intensive plants come to India then the resulting pain and long term damage will be enormous.

Two areas come to mind. One is plants using chemical processes. These are invariably polluting and every effort needs to be made to ensure that such plants are not relocated to India simply to reap the arbitrage to be gained from the low cost of compliance in India.

The second is that Holy Grail of electronics capability, setting up chip fabricators. Not only do these cost billion dollars plus, they consume enormous amounts of water and power.

In the past, "fabs" (fabricators) have been shifted from Japan to Southeast Asian countries like Malaysia but that has not put the host country in the league of leading electronics powers. It is Taiwan that has built the entire eco-system for fabs and reaped the benefits.

There are of course two classical shortcomings preventing India from becoming a manufacturing power - regulatory cost and inadequate infrastructure - which are too well known to need elaborating.

Assuming that these hurdles will be steadily overcome, emerging as a manufacturing power will still require conceiving and developing in India before things can be made in India.

© 2025

© 2025