It is not ownership but the way banks are structured and run that is important for financial sector health, notes Jaimini Bhagwati

The Indian government is persistently advised to reduce its ownership in public sector banks to below 50 per cent.

This is to be expected given that non-performing assets of PSBs have risen to alarming levels.

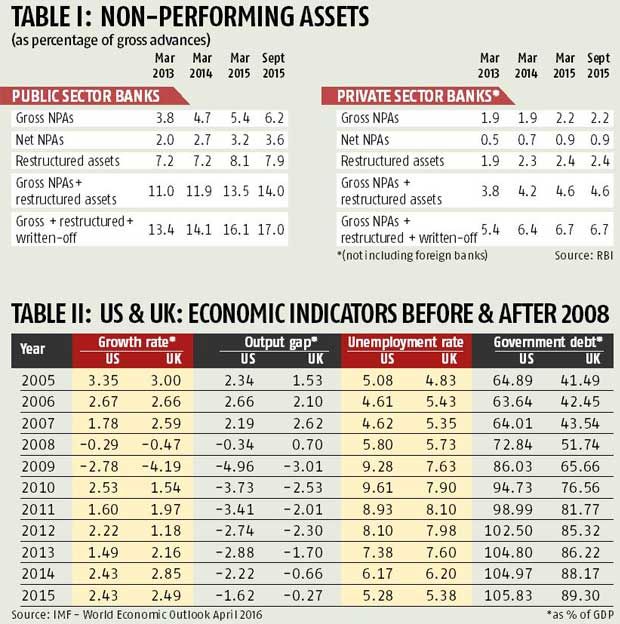

Table I shows that non-performing assets of PSBs are considerably higher than comparable numbers for private banks.

According to those who would privatise Indian PSBs, tax-payers would be less exposed to the risk of recapitalising these banks at periodic intervals.

Additionally, private banks are assumed to be more efficient at intermediating between depositors and investors.

However, it needs to be underscored that private Indian banks are wary of lending at longer maturities.

Consequently, the bulk of infrastructure-project lending in India has been provided by PSBs.

It is the possibility of systemic financial sector breakdown and/or the potential wrath of depositors who may incur losses which compels governments to provide capital to publicly/privately owned banks which are exposed to closure because of excessive leverage.

Therefore, it is not ownership but the way banks are structured and run that is important for financial sector health.

Table II lists the higher unemployment, lower growth rates and consistently negative output gaps in the US and the UK post the 2008 financial sector breakdown.

The sharply higher government debt to gross domestic product ratios have been accompanied by risky unprecedented monetary policies which have bloated the balance sheets of the central banks in these two countries.

The US Federal Reserve’s assets which include mortgage backed securities have gone up from seven per cent of gross domestic product in 2008 to 20 per cent in 2015.

The Bank of England’s assets have risen from about six per cent of GDP to 27 per cent in 2015.

The 2008 crisis was triggered by the liquidity-solvency problems of large private US-UK banks.

If the US and the UK economies had grown annually at 2.5 per cent between 2008 and 2015, compared to what they actually did, simple addition of growth foregone in these eight years would amount to 10.4 per cent and 11.8 per cent of GDP respectively.

Assuming all taxes plus social security contributions add up to 30 per cent of GDP, the corresponding amounts that the US and UK governments could have collected would have been three per cent and 3.5 per cent.

If the Indian government is compelled to provide say Rs 4 lakh crore (Rs 4 trillion) to recapitalise PSBs that would be about 2.8 per cent of 2015-16 GDP.

Although these estimates are simplistic, it is evident that the last financial crisis in the US and the UK was at least as costly, as a percentage of GDP, as the anticipated recapitalisation of Indian PSBs.

On 12 April, the US Federal Reserve and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation stated that eight of the largest US banks including JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America do not have 'credible' plans for winding down without disrupting markets.

And, this is a serious threat to the 'financial stability of the United States'.

In addition to size it is complexity which is at the root of the risks posed by the “too big to fail” banks.

Clearly, it would be incorrect to attribute all negative economic consequences post 2008 to the financial sector crisis. It is abundantly clear though that given regulatory connivance-negligence-forbearance international private banks would keep playing the same game -- 'heads' bank management wins and 'tails' tax-payers lose.

In India we should be concerned about booty sharing relationships across political elites, business houses and management in PSBs/cooperative banks.

The required reforms include promotion of transparency and competitive abilities in PSBs.

Now that the Banks Board Bureau has been set up it is likely that a higher proportion of managers with integrity and ability would be appointed in Indian PSBs.

Some would say that this would just not be possible as long as government remains a majority share-holder.

The BBB should be autonomous and promote competition between PSBs and private banks.

Concurrently, it is imperative that senior government officials have basic educational qualifications in economics-finance and a modicum of domain-market knowledge since they make the final recommendations for senior PSB appointments.

To summarise: (a) greater transparency in PSB appointments at senior management levels of Executive Director and above;(b) reduction overtime in the number of personnel at junior levels (to increase teeth to tail ratio); and (c) a measure of performance linked remuneration would make our PSBs less addicted to financial support from government.

Jaimini Bhagwati is a professor at ICRIER.

© 2025

© 2025