When the Indian economy tanked in 1991, it did so because it ran out of foreign exchange. Today, it is tanking because it has run out of rupees even as the foreign exchange granary is overflowing, says T C A Srinivasa-Raghavan.

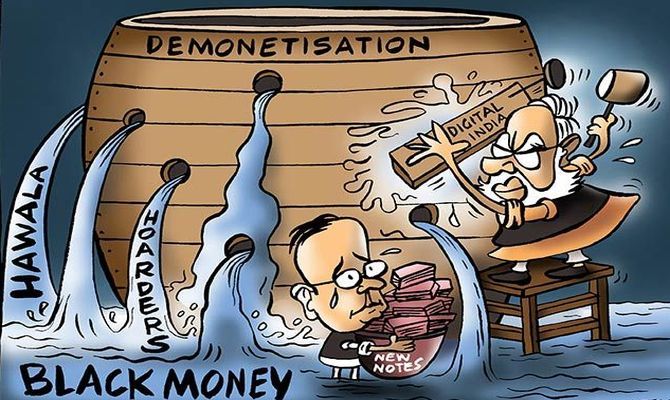

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

Everyone says the Indian economy is in crisis.

Everyone has also agreed that bad policy, on one hand (demonetisation), and bad practice, on the other (GST implementation), have caused it.

Now two very old Bharatiya Janata Party politicians, Subramanian Swamy (78) and Yashwant Sinha (approaching 80), have suddenly gone apeshit. They have prophesised doom.

Mr Swamy’s ire is understandable. He wanted to be finance minister but was not acceptable to the prime minister.

Mr Sinha’s anger is less understandable. He was finance minister from 1998 to 2002. His handling of the economy wasn’t quite masterclass.

Nevertheless, he has come out all guns blazing. To what end it is not at all clear.

This has made the worst finance minister of this century very happy. “I told you so” is his smug response. He forgets that when the economy started to go down, he was finance minister.

In all this so busy is everyone hyping this odd threesome and their critiques that an even greater irony has been missed. To see why, it is informative to compare the problems of 1990-91 with the current difficulties.

The contrast

When the Indian economy tanked in 1991, it did so because it ran out of foreign exchange. Today, it is tanking because it has run out of rupees even as the foreign exchange granary is overflowing.

In January 1991 India had just $1.1 billion of foreign exchange reserves. Today it has over $400 billion.

But the fiscal deficit then was more than 8 per cent for the Centre. Today it is around 3.5 per cent.

The implication is clear: Between 1985 and 1989 Rajiv Gandhi overspent dollars as well as rupees. Between 2014 and 2017 Narendra Modi has under-spent both.

During Rajiv Gandhi’s time the RBI was willing to lend unlimited amounts to the government, but foreigners were not. For Mr Modi, it is the other way around.

Rajiv Gandhi’s economic policy was based on a recommendation made by L K Jha in 1981. He had said growth could, and should, be accelerated by higher borrowings by the government.

But that recommendation had to wait till 1985 because between 1982 and 1984 India was under the IMF’s fiscal discipline. Then in 1986, Rajiv Gandhi let it rip.

By 1989 India was in trouble. It was an election year. So Rajiv Gandhi ignored all the warnings. Mr Modi, too, seems to have done the same -- ignored warnings.

It is not clear on whose advice Mr Modi acts in the way he does. But it is clear that he has chosen to finance growth by unearthing black money to improve government finances.

That move, as my friend R Jagannathan, editorial director, Swarajya, pointed out, has backfired. When banks are as corrupt and inflexible as they are in India, it is black money that provides the lubrication to the economy.

Mr Modi’s efforts, well-meaning though they are, have dried up this much-needed oil in the piston, which has seized.

The task before the government is, therefore, fairly simple: Get the oil back in.

What must be done?

The key element of the new strategy must be to forthwith undo the damage done to the economy since last November.

With the worst economic setbacks caused by demonetisation behind us, this is not as hard as it seems.

First, Mr Modi needs to tell them to start lending and not worry about their make-believe balance sheets.

This would be an absolutely legitimate exercise of sovereign power. The government, after all, owns most of the banks which, thanks to demonetisation, are flush with funds.

Second, he needs to borrow more from the RBI, never mind the fiscal deficit target. Who legitimised 3 per cent anyway? It may be okay for smaller countries and economies but for India it is an absurdly low number. We can easily go up to 5 per cent.

Third, he needs to fix the GST (Goods and Services Tax) multiple rates problem immediately. Zero, 18 and maybe 43 per cent, if need be, are all we need. This will eliminate most of the problems bedevilling the GST.

Fourth, he needs to raise the turnover limit for the GST to apply to Rs 1 crore from the current, pitiable, Rs 20 lakh.

Informal businesses that do not pay tax have their place in a labour-surplus economy. Those below Rs 1 crore can be asked to pay some flat sum after they register.

Fifth, Mr Modi needs to stop the system of enhanced harassment by tax officials, which was started by the UPA to finance the Congress party’s Salvation Army dream.

This is doing more to create a sense of unhappiness than anything else.

© 2025

© 2025